Women's Iconography in the 21st Century

Welcome to the first digital archive of women's iconography! Here you can find out more about the lives and spirituality of women across the world, who have burst onto the scene of Christianity's most ancient sacred artform in the last fifty years!

Iconography is the oldest sacred art practice in the Christian tradition and was the only artform in use across the global Christian church until the Great Schism between the East and West in 1054. Although Western Christians from a variety of denominations engage with a range of sacred art traditions, iconography remains the only art practice that is used by Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant churches. As such, it is the most widely used, cross-denominational Christian artform in the world.

Throughout their history, icons have been produced in male monastic communities, and in the Orthodox Church belong to a formalized ministry that was not made open to women until the twentieth century. Prior to this period, women could assist male iconographers, including their husbands, in their studios. Nuns would occasionally work alongside monks in neighbouring monastic communities but would be assisting "maestros" in the development of large and complex works of art.

Of course, it is possible that women created icons privately, but it is very difficult to know definitively. Iconographers do not sign their work because they see themselves as divine instruments who record a revelation of a holy figure, or spiritual event, to which they have paid witness.

Iconographers depict these revelations faithfully, using materials, techniques and practices that have been passed down for over two thousand years. These practices are said to have been developed by St. Luke, the Apostle, who painted the Virgin Mary from life. St. Luke's icon of Mary, believed to be the first in history, is said to be housed, and venerated, at the Shrine of Tinos in Greece.

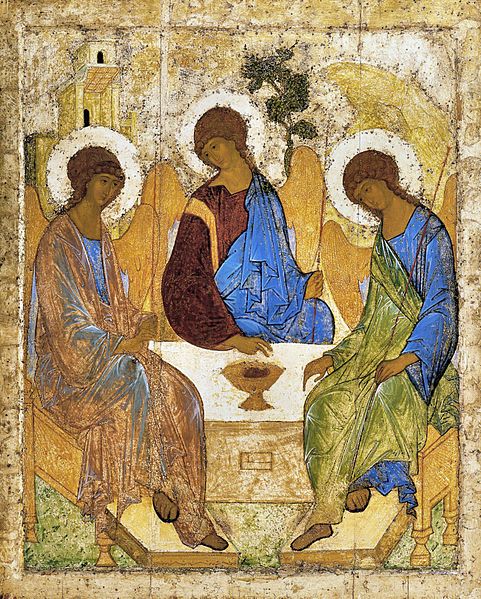

Historical icons are signed with the names of the holy figures they commemorate as marks of the iconographer's humility and veneration. Most male iconographers have also been lost to history with the exception of a few great masters, who shaped and developed the tradition, like Andrei Rublev.

Today, female iconographers outnumber male, and women are holding practice. Yet, they are minimally represented in the canon of images committed to Orthodoxy: there are fourteen sanctioned images of women in a body of approximately five hundred that are formally recognised by the official doctrine of the Orthodox Church.

This project asks: How do women reconcile their faith in the spiritual revelation that is made possible by icon-making with the demand that they use techniques, symbols and practices that have historically been reserved for men and largely depict male figures?

The women featured here are from a variety of denominational backgrounds. They define the icon in different ways. Some remain faithful to parameters laid out by the Orthodox Church, while others bend the tradition to accommodate the techniques they use, or the figures they depict. The scale of their intervention is determined by their religious beliefs, their understanding of the inclusivity of the tradition, and their personalities - how traditional, or how radical, they are.

But they all share one thing in common: they see the sacred image as a window into an invisible world where they can encounter a holy figure from history, who inspires their veneration.

We have divided this archive into two sections: Traditional Iconography, and Iconography-Inspired Sacred Art, the latter of which includes work that does not conform to the stylistic and dogmatic principles set out by the Orthodox Church. Given that traditions evolve over time and across cultures, and congregations, many of these more unconventional images are nevertheless regarded as icons by their creators and viewers. In both sections of this archive, you can find biographies, interviews, and photographic images relating to the careers of women who engage in the iconographic tradition.

This archive is part of a larger project, Contemporary Women Icons funded by an AHRC Impact Acceleration Grant. This project, adminitrated by Lancaster University, promotes the work of female iconographers, fosters interfaith dialogue, and exposes a range of community groups from varied socio-cultural and religious backgrounds to an artform that they might not otherwise have access to.

We want to connect with as many female iconographers as possible, so please get in touch if you would like to be included on this archive. You can also learn more about the history of the icon, and how it is defined, here.

What is an icon?

According to St. John of Damascus: "An icon is a visual image of what is invisible." The iconographer follows a twelve-step process. Each step represents a stage in the individual's journey towards salvation. This process helps them connect with the holy subject, who lives in an unseen world. Indeed, an icon is colloquially known as a "window to eternity." The holy figure looks out at the iconographer and viewer through the window, encouraging both to engage and converse with them in prayer.

For the iconographer to meet their subject, they must use the artistic materials, rituals and techniques that have been passed down from the fifth century and which have been written into Orthodox dogma. If the iconographer is to faithfully depict their subject as they appear in eternity, they must first eradicate any tendency towards self-expression.

By rejecting self-expression, iconographers diverge from other sacred artists, who depict their own feelings about their faith and represent how they imagine the subject looked in their lifetime, rather than in the invisible world.

Since the iconographer represents a world that has different metaphysical laws from our own, their depiction is figurative, rather than literal. The icon combines abstraction and realism to convey the dual nature of the subject as both human and transfigured. The image is deliberately distorted because the spatial and temporal laws of the material world do not apply. Icons use a method called inverse perspective. In this technique, there is no vanishing point where all horizon lines meet.

The iconographic subject's features are unnatural because they have been transfigured. The eyes and ears are disproportionately large to represent the subject's visual perception of God and their reception of his word. Conversely, the mouth is excessively small to indicate that the subject is not concerned with the pleasures of the flesh. The hands communicate through a type of theological sign language that is immediately visible to Orthodox believers.

We say that an icon is "written", rather than painted, because the iconographer "transcribes" the image as it appears to them. They paint their image on a flat wooden board that looks like an altar and hold the brush like a pen. The message of the icon is conveyed through a unique set of symbols that are read by the viewer. For example, the bump on the head of the Christ child denotes his wisdom.

Iconography provides a space where women can transcribe their intimate, and personal, encounters with the divine. In religious institutions where women do not share the power and authority of men, they are nonetheless empowered to share their own revelations of the spiritual world in visual form.

Female iconographers occupy a unique space between modern and traditional ways of thinking and living. They stay connected to their church communities while carving out a space for themselves in an artform that wasn't always welcoming to them. There are many different ways they do this and with varying degrees of radicalism. Some female iconographers create work that would be accepted by the Orthodox Church, while others challenge almost every tenet of the tradition itself. What all of these women share is a belief that they have the right to encounter the holy figure who inspires them through the "window to eternity".

By exploring the work of these artists, we hope you will see how women of faith represent themselves and their communities in spaces where they haven't always been visible. In our workshops, we aim to broaden sacred art to include people and groups that are not often seen on church walls. We're using techniques inspired by iconography, so that members of the public can have the opportunity to spiritually encounter the forgotten women in history who inspire them!